Covirtue Signaling. L’ostentazione di virtù e il public shaming durante la pandemia di Covid-19

Titolo Rivista SOCIOLOGIA DELLA COMUNICAZIONE

Autori/Curatori Oscar Ricci

Anno di pubblicazione 2021 Fascicolo 2020/60

Lingua Italiano Numero pagine 13 P. 82-94 Dimensione file 658 KB

DOI 10.3280/SC2020-060008

Il DOI è il codice a barre della proprietà intellettuale: per saperne di più

clicca qui

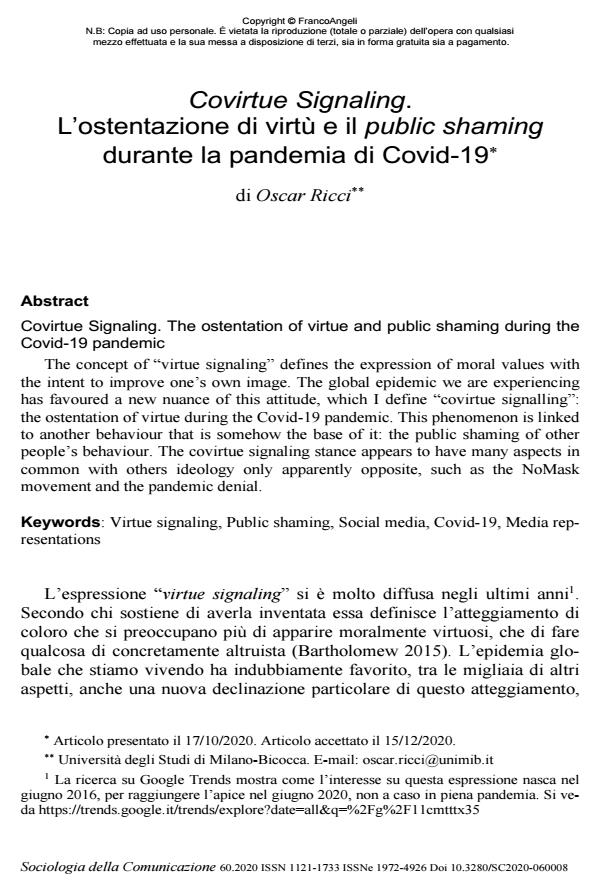

Qui sotto puoi vedere in anteprima la prima pagina di questo articolo.

Se questo articolo ti interessa, lo puoi acquistare (e scaricare in formato pdf) seguendo le facili indicazioni per acquistare il download credit. Acquista Download Credits per scaricare questo Articolo in formato PDF

FrancoAngeli è membro della Publishers International Linking Association, Inc (PILA), associazione indipendente e non profit per facilitare (attraverso i servizi tecnologici implementati da CrossRef.org) l’accesso degli studiosi ai contenuti digitali nelle pubblicazioni professionali e scientifiche.

The concept of "virtue signaling" defines the expression of moral values with the intent to improve one’s own image. The global epidemic we are experiencing has favoured a new nuance of this attitude, which I define "covirtue signalling": the ostentation of virtue during the Covid-19 pandemic. This phenomenon is linked to another behaviour that is somehow the base of it: the public shaming of other people’s behaviour. The covirtue signaling stance appears to have many as-pects in common with others ideology only apparently opposite, such as the No-Mask movement and the pandemic denial.

Parole chiave:Virtue signaling, Public shaming, Social media, Covid-19, Media representations

Oscar Ricci, Covirtue Signaling. L’ostentazione di virtù e il public shaming durante la pandemia di Covid-19 in "SOCIOLOGIA DELLA COMUNICAZIONE " 60/2020, pp 82-94, DOI: 10.3280/SC2020-060008